AFTERLIVES: ARTISTIC AND VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF MASS VIOLENCE

Facilitating a discussion around histories of mass violence and oppression can be tricky, particularly with younger audiences. How can we effectively discuss these topics with students without perpetuating stereotypes, and also elevate the voices of the communities involved? Object-based lessons can be extremely useful in discussing these topics by helping connect students on a personal level.

Several years ago I had the opportunity to virtually visit the University of Michigan History Departments’ course INTLSTD 401.009: Afterlives of Genocide: Artistic, Literary and Visual Representations of Mass Violence. This class focuses on the cultural fascination with what we might term or think of as evil, and in particular when it manifests itself in mass violence, and more specifically, how do we remember, represent, and engage with the violent past individually and collectively. When looking through the collection, I fairly quickly thought of four works in our collection where artists are responding to personal histories of mass violence and oppression: Leopoldo Méndez’s Lo que puede venir (What may come), Patrick Nagatani’s Japanese Children's Day Carp Banners, Titus Kaphar’s, Flay (James Madison), and Ouk Chim Vichet’s, Apsara Warrior (images above). I wanted the students to think about the artist’s personal reflection on these events and how we can see their story told through their work. So often we think about incidents of mass violence with huge, aggregate numbers, like the nearly 2 million people murdered by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, for example. While this is important to understand and remember the horrendous scale of these historical events, it’s also important for us to understand the individual and the personal, and to remember that unique individuals experienced and survived these events. By making it personal, we as viewers and learners can better empathize with the artist, helping us to perhaps better understand what they went through.

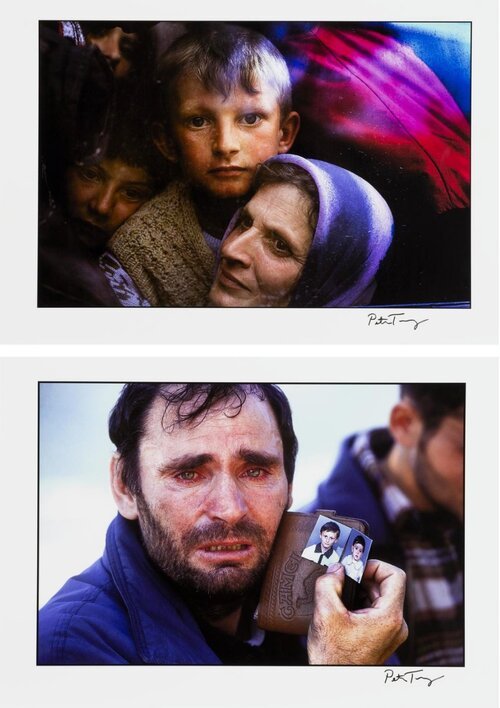

“... if a photo shows dignity and human resilience, it allows for respect and human rights, not just pity and charity. .”

In addition to the question of how artists respond to personal incidents/histories of mass violence, I also wanted students to think about the role museums play in collecting and displaying these works, and what issues arise around this topic. As part of their prep work for the week, I had students read several articles around this issue, like this Artnet article about Shaun Leonardo’s Drawings of Police Violence, or exploring how Museums archive materials from memorials at mass shootings, and how representation of refugees matters. I wanted them to think critically about museums, and to also share my own struggles and processes with choosing what works to look at with them. For example, we have many photographs by Peter Turnley documenting several different refugee crises, such as Kurdish Refugees from Iraq in Southern Turkey during the Gulf War in 1991, or Eritrean Refugees in Eastern Sudan in 1988. These images portray grieving, struggling, unnamed children, women, and men, typically in a refugee camp setting. We have all seen similar photographs in the news and we can probably easily picture them in our heads. Students noted when looking at them, the photographs could be described are somehow aesthetically composed, causing the viewer to think more about how beautiful the photograph is, rather than thinking about the individual(s) in the image. So I asked them, should I be displaying these photographs? They do indeed fit well with the topic of this class, in documenting incidents of genocide and other atrocities, but what does it actually mean for a museum to acquire or purchase a photograph from a photographer, that the photographer makes money on an image of individuals in need of help? How does our class viewing these 20+ years later help these unnamed individuals? The students posited that museums need to add specific context, framing, and transparency when displaying these photographs, as they also argued that hiding them away could be an act of censorship or erasure. They also mentioned that perhaps we should acquire art made by refugees that tell their personal stories and then display those alongside our current photographs to help construct a better-informed narrative. As one of the students remarked, “if a photo shows dignity and human resilience, it allows for respect and human rights, not just pity and charity.”

Check out the class slides here for more information on each work.

We have many photographs by Peter Turnley documenting several different refugee crises, such as Kurdish Refugees from Iraq in Southern Turkey during the Gulf War in 1991, or Eritrean Refugees in Eastern Sudan in 1988. These images portray grieving, struggling, unnamed children, women, and men, typically in a refugee camp setting. We have all seen similar photographs in the news and we can probably easily picture them in our heads. Students noted when looking at them, the photographs could be described are somehow aesthetically composed, causing the viewer to think more about how beautiful the photograph is, rather than thinking about the individual(s) in the image. So I asked them, should I be displaying these photographs?

Top: Peter Turnley, Kosovar-Albanian Refugee During the War in Kosovo, Kosovo-Albanian Border, 1999. Bottom: Peter Turnley, Kosavar-Albanian Refugee, Albanian Border with Kosovo, 1999.